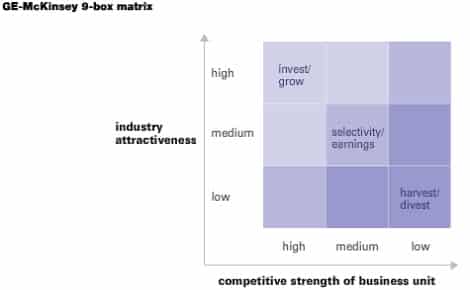

The GE-McKinsey 9-Box Matrix offers any decentralised corporation with multiple business units a systematic approach to help it decide where to invest its cash

IN SEPTEMBER 2008, the McKinsey Quarterly published an interactive audio presentation on the GE-McKinsey 9-Box Matrix.

An outline of this framework is provided below.

1. Background

The 9-Box Matrix follows in the footsteps of Boston Consulting Group’s growth share matrix which was introduced in 1968.

The 9-Box Matrix was developed as part of work that McKinsey did for GE in the early 1970s. At that time, GE had around 150 business units and was faced with the challenge of how to manage such a large number of business units profitably.

The 9-Box Matrix was developed as a result of the realisation that it is important to separate the ability of a business to generate cash from the decision about whether to put more cash into the business.

2. Purpose

The 9-Box Matrix offers any decentralised corporation with multiple business units a systematic approach to help it decide where to invest its cash.

The 9-Box Matrix solves the problem of trying to compare potentially very different business units: one might be capital intensive; another might require high advertising expenditure; a third might have economies of scale.

Instead of relying on the projections provided by the manager of each individual business unit, the company can determine whether a business unit is going to do well in the future by considering two factors:

- attractiveness of the industry; and

- the business unit’s competitive strength within that industry.

3. Using the matrix

(Source: McKinsey Quarterly)

Placing each business unit within the 9-Box Matrix offers a framework for comparison between them.

In order to keep things simple, the framework offers only three investment strategies:

- Invest/Grow;

- Selectivity/Earnings; and

- Harvest/Divest.

Allocating one of these investment strategies to each business unit is a necessary first step. However, it is important to note that two business units that have been given the same strategy will not necessarily be treated in the same way. For example, a strong unit in a weak industry is in a very different situation than a weak unit in a highly attractive industry.

After placing a business unit into one of the nine boxes, there are at least two questions that are worth asking:

- If a business unit is in one category, say “selectivity/earnings”, is there anything that can be done to change its position? That is, would it be possible to move a business unit from the “selectivity/earnings” category and into the “invest/grow” category by making any kind of strategic investments?

- If a business unit is to receive money, what should it do with that money? It is important that money is given with a purpose in mind because the best use of money will vary depending on the industry and on the business unit. For example, advertising to enhance the brand might work for one business unit, whereas investing to increase research and development might work for another.

4. Axes of the matrix

The 9-Box Matrix places “industry attractiveness” along the vertical or y-axis, and “competitive advantage” (otherwise known as competitive position, or competitive strength of the business) along the horizontal or x-axis.

4.1 Industry attractiveness

Industry attractiveness refers to whether the industry is going to do well in the future. Are most players in the industry likely to do well? How easy will it be for the average company in the industry to make profits over the long run?

There are a number of different factors that affect industry attractiveness and those factors will vary in importance from industry to industry, for example: long run growth rate of the industry, current profitability, etc.

The Structure Conduct Performance model or, its more popular simplified version, the Porters Five Forces model both provide a formal approach to look at industry attractiveness.

4.2 Competitive advantage

According to Coyle, the first formal definition of “sustainable competitive advantage” was not determined until the mid-eighties.

In the early days of the 9-Box Matrix, analysts used proxies for sustainable competitive advantage:

- Is the business unit’s market share growing? Maybe we can infer from this something about its competitive advantage.

- How strong is the business unit’s brand equity? That is, how much of a price premium can it charge?

- Is the company more profitable than its competitors?

A business has a competitive advantage when it is able to achieve profits that exceed the industry average. Competitive advantage may be established by offering consumers greater value by way of:

- lower prices;

- differentiated goods or services that justify higher prices; or

- establishing a market niche and achieving a narrow, rather than an industry wide, competitive advantage.

5. Available strategies

5.1 Invest / Grow

A business unit will be in the “invest/grow” category if the prospects for the industry as a whole are attractive and the business unit’s position in the industry means that it is likely to do better than most of the other firms in the industry.

A business unit in this category should be given as much money as it needs regardless of whether it can generate those funds itself.

5.2 Selectivity / Earnings

Business units in this category are given second priority to those in the “invest/grow” category. So, the amount of money spent on business units in the “invest/grow” category will determine how much money is left over for business units in this category.

When allocating money to a business unit in this category, it is important to be selective about where the money is spent and monitor earnings closely. With the right combination of strategies, it may be possible to move the business unit into the “invest/grow” category.

In this part of the matrix it is a good idea to be careful. If the business unit doesn’t improve then it may be best to invest money elsewhere.

5.3 Harvest / Divest

A business unit will be in the “harvest/divest” category if it is in an unattractive industry and its competitive position is weak.

There are two suggested strategies:

- sell the business unit (divest); or

- increase short-term cash flows as far as possible, even at the expense of the business unit’s long term future (harvest).

For more information on consulting concepts and frameworks, please download “The Little Blue Consulting Handbook“.