ON WEDNESDAY November 23rd, an auction of German government bonds (known as “Bunds”) managed to sell only €3.6 billion out of a total €6 billion worth of Bunds on offer (source: Economist).

Germany is one of the most financially stable countries in the Euro-zone, so its failure to sell all of its Bunds is worth examining. In the context of an ever worsening European sovereign debt crisis this could be cause for concern. However, there are three reasons why the news does not raise concerns about Germany. Firstly, the German Debt Agency (Finanzagentur) normally retains part of any new Bund offer, so a partial sale of Bunds is pretty standard. Secondly, German Bunds are expensive. With a current 10-year Bund yield of only 2.26% it is no wonder that investors have a weak appetite for German debt. Thirdly, European banks are currently focused on building their balance sheets not on lending. European banks have until the end of June 2012 to get their core capital ratios up to 9%.

While Bunds may still smell sweet, weak financial markets in Europe are a cause for concern.

Weak financial markets increase the risk that one or more European banks will fail. In fact, one already has. Dexia fell victim to the Euro-zone debt crisis in October and was rescued by Belgium and France. This is particularly concerning because only a few months ago Dexia was rated 12th safest bank in Europe by European Union stress tests. How could Dexia fail? The short answer is, surprisingly easily. Dexia has around $700 billion on its balance sheet, but like many banks it requires access to short term funding. With banks becoming increasingly nervous as a result of weak credit markets, Dexia simply failed to secure the short term funding it needed to stay afloat. Dexia’s problems stemmed in part from its exposure to around $25 billion of Greek debt.

There is every likelihood that Greece and other countries may default on their debts. Greece and Italy both have a debt/GDP ratio exceeding 100%, but they are by no means the only countries that need to balance their books. Debt levels are worryingly high in Japan, the UK, USA, Portugal, Ireland and Belgium (among others). Greece represents less than 2% of the EU economy, but the effect of a Greek default could be worse than the sub-prime mortgage crisis. There are three reasons for this:

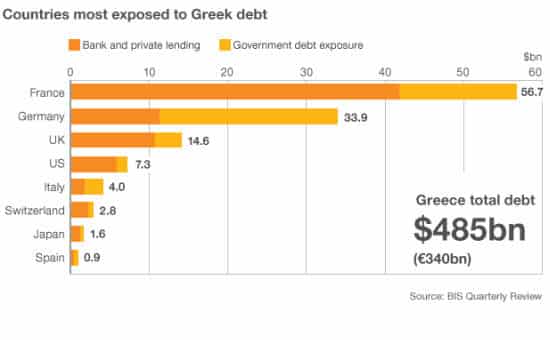

- Integrated financial markets: As we saw during the sub-prime crisis, credit markets are highly integrated. France alone is exposed to more than $56 billion of Greek debt (see graph below). If Greece defaults then this could drive a number of European banks into bankruptcy;

- Nervous markets: As it is not clear which European banks may fail, nervous banks may stop lending money to each other. As a result, this would drive up interest rates or, in the worst case, may completely stop the flow of short term credit and put the viability of many banks and businesses in jeopardy;

- The Domino Effect: Greece is the first domino. Following a Greek default, financial market vultures will turn their greedy attention to other beleaguered countries. Italy may be second in line.

🔴 Like this article? Follow us now on LinkedIn to stay in the loop and connect with other readers.

Sharpen your edge in consulting