Lack of a sustainable ‘business engine’ is a Social Enterprise’s Kryptonite

IT’S a charity … It’s a for-profit … No, it’s a social enterprise!

Social enterprise is on the rise (the number of social enterprises in Australia has grown by 37% in the last 5 years). Just like a regular business, but with one key difference; a social enterprise operates for social, environmental or cultural purposes rather than with a view to profit.

In the third issue of the SVA Consulting Quarterly, Duncan Lockard explains that a social enterprise, despite having a social mission, should also have a commercial business model.

Identifying the business model

All social enterprises have a business model. The business model is simply the method that the enterprise uses to create and deliver value to members of the community in exchange for payment (in cash or in kind).

If a social enterprise does not understand its business model then its financial performance will suffer, and this will undermine its ability to achieve its social goals. On the revenue side, insufficient focus on marketing can lead to weak sales growth. On the cost side, lack of operational discipline can result in inefficiency and high costs.

Without a sustainable business model, a social enterprise is likely to run up against three problems. Firstly, the enterprise will remain dependent on donations and subsidies, which places it in a vulnerable position. Secondly, since the underlying business model is not viable, it will be difficult for the enterprise to grow and expand its social impact. Thirdly, if community support for the enterprise is merely sustaining a poorly run business rather than creating social impact then a fair question might be: “should the enterprise continue to exist?”

Assessing sustainability

Determining whether a social enterprise has a sustainable business model can be difficult. Lockard refers to this as the “the haze of the hybrid organisation”.

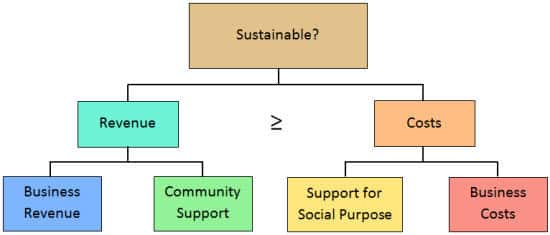

Basic formula:

The basic formula for business model sustainability is pretty simple: business revenues need to exceed business costs.

Complication:

The complication is that a social enterprise will typically generate income from both business revenue and community support, and will incur expenses that include both standard business costs and costs associated with supporting the social purpose.

To assess the performance of a social enterprise, Lockard explains that “[t]he first step is to see through the haze of the different incomes and costs and assess the ‘business engine’ that sits at the core.” This requires identifying ‘commercial’ revenues separately from ‘non-commercial’ revenues, and doing the same for costs.

The case of the Nundah Co-op

SVA Consulting has a lot of experience working with social enterprises, and Lockard shares a recent case of the Nundah Co-op. Based in Brisbane, the Nundah Co-op runs a café and parks maintenance service. As a social enterprise, its aim is to provide employment opportunities for people with intellectual disabilities. This is a valuable social goal, but the Co-op faced a problem. It had been running losses of around $20,000/yr for several years. Could further losses be justified?

SVA Consulting’s analysis showed that although Nundah Co-op’s total revenue was less than total costs, its business revenues exceeded business costs. This showed that the Co-op’s core business model was sustainable, and so the $20,000 subsidy paid by the Co-op’s parent organisation could be justified since it covered the Co-op’s additional costs in meeting its social purpose.

For truth, and justice, and the American way

To read more about SVA’s work with sustainable social enterprise: click here.

To read Issue 3 of the SVA Consulting Quarterly: click here.