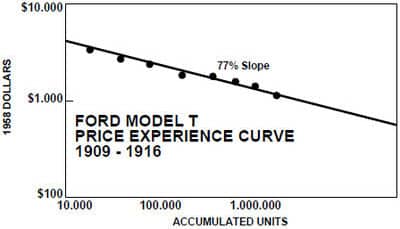

The Experience Curve captures the relationship between increasing production experience and declining costs

(Source: Flickr)

Background

The Learning Curve, the concept which predates the Experience Curve, was first described by German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus in 1885 as part of his studies into human memory.

In 1936, T.P. Wright described the effect of learning on production costs in the aircraft industry showing that required labour time dropped by 10 to 15 percent with every doubling of production experience.

In 1966, Bruce Henderson and the Boston Consulting Group conducted research for a major semiconductor manufacturer, in which they introduced the concept of the Experience Curve and revealed that unit production costs fell by 20 to 30 percent every time production experience doubled.

In essence, the Learning Curve and the Experience Curve capture the same big idea: performance improves with experience in a fairly predictable way.

How do the two curves differ?

In his 1968 article, Bruce Henderson distinguished the Experience Curve from the Learning Curve by explaining that the Learning Curve relates only to labour and production inputs, while the Experience Curve focuses on total costs.

On the surface his explanation sounds reasonable, but when you think about it what he was really saying is that the Experience Curve is the same as the Learning Curve, just with a slightly broader focus.

Henderson’s distinction was a clever conceit, and his trick allowed the Boston Consulting Group to take credit for an idea that had been in circulation for more than 80 years.

Legitimate or not, the rebranding exercise was effective and has meant that since 1966 the concept has been widely known in management and business circles as the Experience Curve with due credit going to Bruce and the Boston Consulting Group.

This article is entitled “Experience Curve”. We didn’t want to rock the boat.

Experience Curve Explained

The Experience Curve captures the relationship between a firm’s unit production costs and production experience. Research has shown that a firm’s costs typically fall by a predictable amount for every doubling of production experience.

Unit production costs tend to decline at a consistent rate as a firm gains production experience, however the rate will typically vary from firm to firm and from one industry to another.

The interesting thing about the Experience Curve is not that a firm’s performance improves with experience, we would expect as much, but instead that performance tends to improve with experience at a predictable rate.

This is surprising. What could explain such consistency?

Learning from Experience

In his 1968 article, Bruce Henderson noted that:

“… reductions in costs as volume increases are not necessarily automatic. They depend crucially on a competent management that seeks ways to force costs down as volume expands. Production costs are most likely to decline under this internal pressure. Yet in the long-run the average combined cost of all elements should decline under the pressure for the company to remain as profitable as possible. To this extent the [Experience Curve] relationship is [one] of normal potential rather than one of certainty … ”

While falling costs may not be inevitable, the Experience Curve effect is pervasive and so declining costs must result from some kind of innate human and organisational factors rather than from, say, the brilliance of a rock star management team or the well power pointed recommendations of a top consulting firm.

Where do the reduced costs come from?

While by no means an exhaustive list, factors that may contribute to the Experience Curve effect include:

- Labour efficiency – As employees at all levels of the organisations gain more production experience they gain skills, learn shortcuts, and find ways to produce more with less.

- Standardisation – Over time processes and product parts may become standardised allowing for more streamlined production.

- Specialisation – As production volume increases a firm is likely to hire more employees, allowing each of them to specialise in a narrower range of tasks.

- Optimised Procurement – As a firm gains production experience it will learn about its suppliers and what they have to offer, which will allow it to optimise its procurement practices.

- Product Refinement – A firm may engage in significant R&D and marketing prior to and during its initial product launch, but as it learns more about the product and its customers it will be able to refine the product for the requirements of the market. This may allow a firm to reduce ongoing R&D and marketing costs.

- Automation – Increased production volume may lead to the adoption of more automated and advanced production technology and IT systems.

- Capacity Utilisation – If a firm has incurred large fixed costs, then increasing production will allow it spread these costs across a larger number of units.

- Equipment Upgrades – Higher production volumes may justify investment in more advanced equipment.

Implications for Strategy

The Experience Curve effect shows that a firm’s production costs decline in a fairly predictable way as it gains production experience.

What are the implications for corporate strategy?

In 1968, in light of BCG’s research, Bruce Henderson took the view that a firm should price its products as low as would be necessary to dominate their market segment, or else it should probably stop selling them. The same year BCG also developed its now famous growth share matrix, a framework that recommends allocating resources within a firm towards products that are, or are going to become, market leaders.

The clear and resounding message from Henderson and BCG was “dominate the market or don’t bother”.

The thinking behind this rather clear-cut view was that a company with market share leadership would be able to gain production experience more quickly than its rivals and so would be able to achieve a self-sustaining cost advantage.

As it turns out though, pursuing market share leadership will not always be beneficial. There are four countervailing forces that can neutralise the benefits of this strategy.

Firstly, market share may not confer a cost advantage since firms can learn not just from production experience but also from books, courses, formal training, conferences, reverse engineering, talking to suppliers and consultants, and by poaching staff from the competition.

Secondly, if multiple firms pursue market share leadership at the same time then this can create intense rivalry and destroy industry profitability.

Thirdly, new entrants can often avoid going head to head with the market leader by creating more advanced products or using more efficient production technology. This can allow new players to leap frog the competition and force existing firms to play catch up by investing heavily in R&D, forming strategic alliances or acquiring the upstarts for a princely sum.

Fourthly, even if market share leadership does confer a cost advantage there are other ways to compete effectively. Firms can gain an edge by creating unique products or by focusing on niche segments of the overall market (see Porter’s Generic Strategies).

So, where does this leave us?

Well, a firm that aims to be the cost leader within its industry will probably want to pursue market share leadership since the Experience Curve effect and economies of scale will allow it to reduce costs.

On the other hand, a firm that aims to compete by providing a unique offering or by serving a market niche may find the pursuit of market share leadership detrimental. A firm that provides unique or targeted products will generally be able to charge higher prices and this will limit potential sales volume. If it makes its products more generic in an attempt to appeal to the mass market, then this could destroy the “je ne sais quoi” which made the firm successful in the first place (see “Stuck in the Middle”).

Market share leadership can work, but it will not be the correct strategy in every situation.