It is not like I knew Peter well – as a real live person. In fact, I only met him once – in Claremont – as a very old man. That said, I always found it rather funny and more than touching that for a man who helped chart the academic progression of American management studies, he never lost a heavy German/Austrian accent. “Zis ist Peter Drucker” – the message he recorded on his home answering machine – was a cause of much delight at one point in my life, particularly because my father spoke with an upper class English accent, and my aunt with a highly Californianized German one.

Peter was the husband of my father’s eldest sister, Doris. My father was not a fan. Apparently in my family’s frantic transition from central Europe via England and then to the U.S. during the 1930’s, the relationship between the two men became fraught with tension and personal squabbles whose original genesis was odd, to say the least. The cause of a decades long civil war apparently started over Peter’s heavy handed English language instruction to my father (then in British boarding school while Peter was a business journalist in the UK). It continued over the course of a lifetime, fuel added to the fire by envy, competition and academic success. My father thought it was fundamentally “unfair” that the End of Economic Man was published to take advantage of the announcement of the Stalin-Hitler Pact. While Peter taught at NYU, my father was at the New School. Peter followed an entrepreneurial academic path. My father a journalistic and creative one. My father also had a fundamental disgust that Drucker covered up the fact that he was Jewish. In fact, he frequently referred to my uncle as “that ugly man” and (more than once) as an “unapologetic fascist.”

Perhaps because of that, I read all of Drucker’s major works as an act of rebellion by the time I entered college (in the mid 80’s). And at that point Drucker was already being redefined, as well as slightly shelved, by the newer generation of management consultants who took his place. I also experienced his work about the “third way” by being exposed to it directly in managing a non-profit as one of my first jobs out of school. Even at the time, I thought it represented a way to redefine his voice in a way that I believe will continue to be redefined in the century “after Drucker”. He was shifting from writing about focussing on management for the manufacture of profit to management to profit society. At that point in his life he also began to believe that his work was being misinterpreted. By the turn of the century, this was much more evident, at least in private. According to my aunt, who accepted the Medal of Freedom on his behalf (because at that point he was too sick to travel), Drucker was also unbelievably embarrassed that “management by objective” had been used to justify the Iraq War.

Interpreting Drucker’s intended meaning has been, as a result, a journey that I have undertaken as part of understanding my family and myself as much as it is about management.

My perspective on Drucker started with my curiosity about why he felt that nepotism was a fundamental evil. As a child I often thought this was because of the ancient family feud between my father and my uncle.

But as an adult, my understanding became more nuanced.

Drucker was, at least in my mind, a business anthropologist. He sought to understand and explain company culture in a way that is akin to an expat trying to understand the culture of a new country. He was no less hurt than most European Jews were about being betrayed by their home countries on the basis of an intangible idea (religion). His writing about nepotism, for example, was I believe a fundamental criticism of the German “Mittelstand” and how easily companies designed for one purpose (efficient production and profit) can be perverted by politics, as happened in Europe with the rise of Hitler. Later Drucker writing on the importance of managers getting out of the way and letting employees do the work they were there to do, as well as his early interest in an IT enabled and remote working environment, was also heavily influenced by the background of a man who relied on his entrepreneurial skills and distrust of office politics to survive in a world hostile to immigrants.

By the time Drucker shifted in focus at the end of his career, he had clearly also become concerned with the way that American corporate life was rapidly undermining the stability of American society achieved after WWII. “The third way”, and his argument for the professionalization of non-profit work, was in some ways a bit of an apology for Drucker’s early celebration of corporate culture in the U.S. His writing on executive pay, for example, was clearly a reaction to the beginnings of private sector greed that has become a major political topic of our new century.

Ultimately, Drucker was a man who sought to make sense of a world caught between politics, society and culture operating within the framework of something else – the corporate structure. While the specific issues that our society is called upon to face are of course different at the beginning of this new century, I also feel that the things he wrote about have never been more pertinent and relevant.

Marguerite Arnold is an entrepreneur, author and third semester EMBA candidate at the Frankfurt School of Finance and Management.

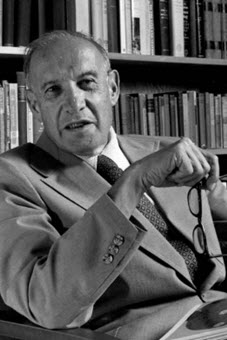

(Image Source: Benandju)