When I studied economics at Sydney University in the early 2000s and financial economics at Oxford in the early 2010s, I learned pretty much the same thing about money; very little.

Money is not really respected in academia, and so most of the attention tends to focus on other topics: the interaction between buyers and sellers, the structure of industries, statistical modelling, the valuation of financial assets, and so on.

I now know that money is simply any asset that is generally accepted as a means of payment to settle debts. At different points in history, different things have been used for this purpose: salt, rum, cigarettes, precious metals, and fiat currency.

The smaller the group of people, the easier it is to reach agreement on what to use as money. Within my family, chocolate can work. Within Australia, Australian dollars are acceptable. However, how does one sovereign settle debts with another sovereign?

The US dollar is the global reserve currency, and is regularly used in global trade. However, it comes with one unfortunate drawback. Only the US Federal Reserve can print US dollars, and they can print as many as they want. In the long run, it would seem fairer to base the global monetary system on an asset that is not produced exclusively by any one nation and which people are generally willing to accept as valuable.

In this short article, we will provide a brief history of today’s global monetary system, explain why central banks aim to produce consumer price inflation, and consider some of the potential consequences.

Bretton Woods System: 1944 – 1971

The forerunner of today’s monetary system was the Bretton Woods System, which was forged at the end of World War II by 44 allied nations in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire in July 1944.

The principal goal of the Bretton Woods System was to create an efficient foreign exchange system in order to promote trade and economic growth while at the same time preventing countries from engaging in competitive currency devaluations. Since the US held most of the world’s gold reserves at the time, it was agreed that the US dollar would be convertible into gold at a fixed price of US$35 per ounce, and other global currencies would be pegged to the dollar at a fixed exchange rate.

The Bretton Woods System created a kind of monetary discipline. If the US tried to gain a trade advantage by printing too many dollars, the dollar would devalue and other countries would rush to convert their dollars for gold. (Incidentally, many countries did just that in the 1960s.) If another country tried to gain a trade advantage by printing too much of its own currency, its currency would devalue and it would be forced to sell its US dollar reserves in order to defend the exchange rate peg. If this proved insufficient, it might also need to raise domestic interest rates in order to attract inflows of foreign capital. This would increase the cost of doing business domestically and reduce the country’s international competitiveness.

Petrodollar System: 1971 – Present

In 1971, in the midst of the Vietnam War, President Richard Nixon ended the US dollar’s convertibility into gold. By taking America off the gold standard, the US dollar became a fiat currency, deriving its value not from a claim on gold but from the stability and creditworthiness of the US government, the tax collecting power of the Internal Revenue Service, and the restraint of the Federal Reserve in limiting the supply of dollars. (It did not become legal for Americans to own gold until 1975.)

Although the US dollar lost its gold backing, it has remained the global reserve currency. According to the IMF, the US dollar accounts for more than 60% of central bank foreign exchange reserves, worth more than $6.7 trillion.

A key reason that the US dollar continues to play a central role in the global monetary system is that oil is priced in dollars. In the early 1970s, Saudi Arabia and other OPEC countries agreed to set oil prices in US dollars. As a result, the US dollar is the most accepted currency in global trade. Around 90% of foreign exchange trading involves the US dollar and, by the end of March 2019, US dollar denominated loans to non-bank borrowers outside America exceeded $11 trillion.

Under the Petrodollar System, each country has an incentive to devalue its currency. There are at least two reasons for this impulse. Firstly, a currency that weakens over time allows a country to improve its relative competitiveness in global trade. And secondly, it allows the government to engage in a certain amount of deficit spending.

Since most advanced economies have adopted a freely floating exchange rate (e.g. Australia, Canada, the EU, Japan, Mexico, the UK, and America), when they devalue their currency it tends to weaken in the foreign exchange market, making the country more competitive in global trade. For example, imagine Coca-Cola (an American company) sells cans of Coke in Australia. If they sell for A$1 each and the exchange rate is A$1:US$1, then Coca-Cola would be able to bring home one US dollar for each can of Coke it sells. If the US dollar weakens and the exchange rate becomes A$1:US$2, then Coca-Cola would be able to bring home twice as much.

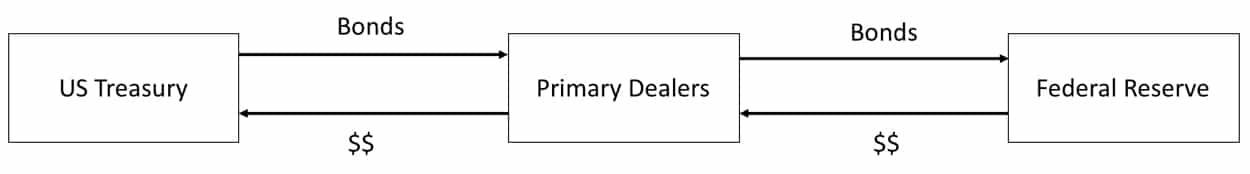

In an environment where currency devaluation is the norm, national governments also have an opportunity to enrich themselves through deficit spending. For example, if the US government spends more than it collects in taxes, it can finance the budget deficit by selling bonds. (The bonds are sold to primary dealers, who can then on sell the bonds to the Federal Reserve, who buys them with newly printed money.)

The US government can spend the newly printed dollars to purchase oil or other goods and services. However, as the new currency gets spent into circulation, prices tend to be bid higher. As a result, the US government is able to inflate away its debts by repaying bondholders in the future with currency that has less purchasing power.

Maintaining Price Stability

While each country has an incentive to devalue its currency, excessive currency devaluation poses four risks that have the potential to create instability on a national or global scale.

- Excessive currency devaluation tends to increase trade tensions which have the potential to spiral out of control into fully-fledged currency wars where a large number of nations simultaneously try to devalue their currency at the same time.

- Countries that are net oil importers will end up paying a lot more for oil (since it is priced in US dollars) leading them to suffer increasing trade deficits.

- Businesses or governments that have a large amount of US dollar denominated debts may have trouble repaying those debts if their revenues are denominated in the local currency.

- Countries may experience hyperinflation, which means rapidly rising consumer prices. This is a problem because it forces households and businesses to divert energy away from productive activity and towards managing and avoiding the cost of inflation.

As a result, central banks in most advanced economies try to avoid excessive currency devaluation by adopting a monetary policy that targets a low and stable rate of inflation. This typically means keeping a lid on consumer prices measured using an index like CPI or PCE.

To give you a snapshot, here are the central bank inflation targets in a few of the world’s leading economies:

- Australia: RBA inflation target is 2-3%

- Canada: BOC inflation target is 1-3%

- China: PBOC inflation target is around 3%

- France: ECB inflation target is ‘below but close to’ 2%

- Germany: same as France

- Italy: same as Germany

- Japan: BOJ inflation target is 2%

- New Zealand: RBNZ inflation target is 1-3%

- UK: BOE inflation target is 2%

- USA: Fed inflation target is 2%

Do you notice how consistent these inflation targets are?

It is clear that central banks around the world are highly coordinated in their approach to monetary policy, and aim to produce a low and stable rate of consumer price inflation.

In this context, it is worth noting that rising prices also tend to show up in asset price bubbles, such as the Japanese Asset Price Bubble of 1986 to 1991, the Dotcom Bubble of the 1990s, and the US Housing Bubble of 2002 to 2006. While focusing intently on consumer prices, central banks tend to ignore rising asset prices. At first it seems strange that they would do this. However, it eventually becomes clear. If consumer prices rise unexpectedly, this reduces consumer spending power and economic activity. However, if asset prices rise unexpectedly, this makes households more creditworthy. This allows banks to earn more profits by growing their loan book, and allows the government to collect more taxes.

Of course, some countries do have different monetary policies. Countries that are too small or unstable may adopt the currency of another nation (e.g. Vatican City, British Virgin Islands and Panama). And countries that are export dependent and highly sensitive to exchange rate risk may peg their exchange rate to the US dollar or another stable currency (e.g. Hong Kong, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates).

Currency Wars or Hyperinflation

Can the world avoid excessive currency devaluation and the associated risks indefinitely? Never say never. However, in recent times, the cracks in the global monetary system are beginning to show.

Over the last two months, the US Federal Reserve has pumped more than $2.4 trillion of new money into the system.

However, despite this, America has not yet seen rising consumer price inflation. Does that mean hyperinflation is not on the cards?

Well, since inflation is intended to indicate the decreasing purchasing power of a nation’s currency, instead of measuring prices we could instead measure “inflation of the money supply”. If the rate at which money gets spent (its velocity) is falling, then an increasing money supply may not show up in higher prices. At least not right away.

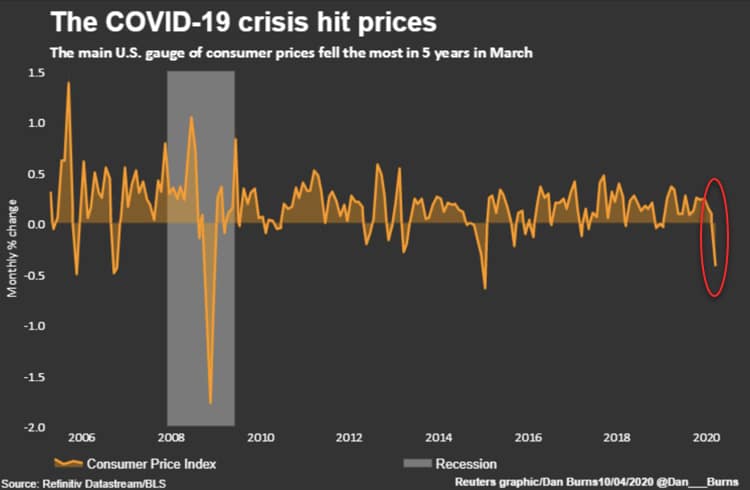

Since many people are in lockdown, working from home, and foregoing their usual activities, the rate of spending has plummeted. So much so, that average consumer prices in America fell in March.

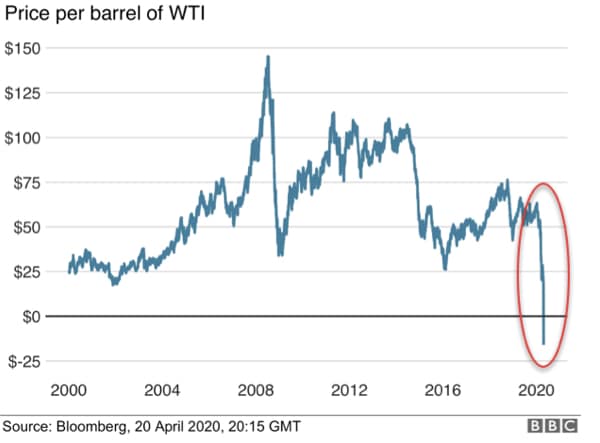

On Monday April 20th, the price of oil (West Texas Intermediate) fell by 300% reaching an unprecedented negative $37.63 per barrel. If you had storage available, you could have been paid to take delivery.

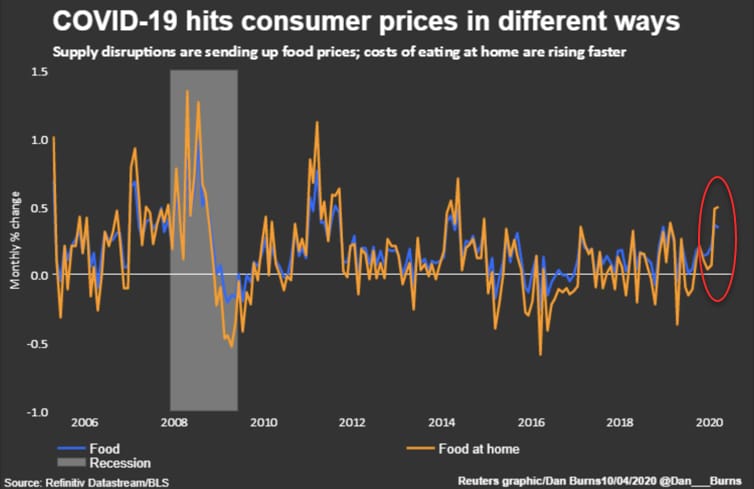

Despite most prices falling due to lack of demand, some prices have actually risen. Most notably, food prices. In March, American food prices rose at their fastest rate since 2014. Many other countries have also seen rising food prices: e.g. Australia, UK, China, India.

Despite the high levels of uncertainty brought about by COVID-19 and the resulting lockdowns, the health crisis will eventually pass. At that point, we will have to deal with the large number of people who have lost their job. Economists surveyed by Refinitiv expect the US unemployment rate for April to exceed 16%, the highest level since 1939.

Given that consumer spending accounts for roughly 70% of the American economy, it may take many months or even years for things to return to normal.

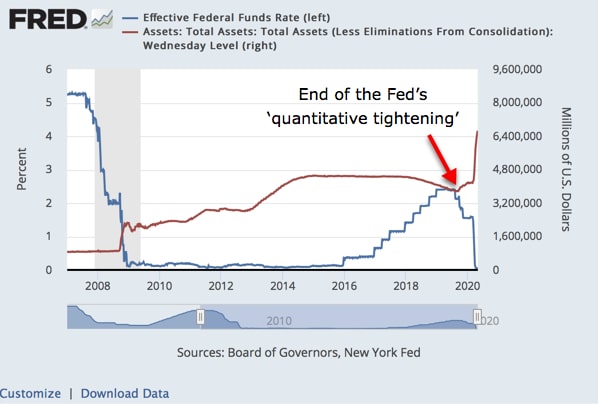

However, when confidence eventually returns and the rate of spending starts to rise, at that point, the Federal Reserve will not be able to reduce the money supply by shrinking the size of its balance sheet. We can predict this with a fair degree of confidence because their previous attempt at ‘quantitative tightening’ failed in September 2019 when repo rates jumped to 10%.

As a result, America’s increased money supply is here to stay. When it starts getting spent into circulation, consumer prices may rise rapidly.

To make matters worse, America is not the only country printing large amounts of new money. During March and April, using coronavirus as a pretext, multiple countries and monetary unions engaged in ‘quantitative easing’ including the UK (£645 billion), Australia (A$5 billion), Canada ($250 billion), China (RMB56.1 billion), and the EU (€750 billion).

Germany’s Constitutional Court has taken issue with the large scale money printing, ruling that the European Central Bank’s QE program partially violates the German constitution. The court ruled that since the ECB does not apply a “proportionality” test to its Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP) it fails to take into account negative economic side-effects, and so does not fall within the ECB’s mandate of ensuring price stability.

If all of this money printing by a large number of countries is not yet considered a currency war, then you would be forgiven for thinking that we are definitely headed in that direction.

Final thoughts

Many countries (America, UK, Australia) have already entered an economic downturn, and many commentators believe this will be the worst downturn since the great depression. There is also a real possibility of excessive currency devaluation leading to hyperinflation and currency wars.

In this context, what should the average individual or business do to protect themselves?

In answering this question, we should be clear about the risks:

- Liquidity risk – the possibility of reduced access to cash;

- Inflation risk – the possibility that cash will lose its purchasing power.

Liquidity risk means that a business or individual may suffer reduced access to cash due to reduced sales revenue, unemployment, or reduced access to funding markets. This is a problem to the extent that they have large fixed costs like rent or interest payments.

One way to manage liquidity risk is to increase your stock of savings. However, if the economic downturn turns out to be severe, then you will also be exposed to increasing counterparty risk with the bank. If banks are at risk of failing then they may close for a period of time or institute bank bail-ins. You could lose access to your deposits, and so you may want to keep part of your savings in a safe place outside the banking system.

In many countries bank deposits are guaranteed by the government up to a certain limit. In America, the FDIC insures each depositor for up to US$250,000. In the UK, the FSCS insures each depositor for up to £85,000. And in Australia, the FCS insures each depositor for up to A$250,000.

Bank guarantees reduce counterparty risk, but create massive inflation risk. Since many countries have already embraced quantitative easing, there is a 97.3% chance that bank bailouts would be paid for with newly printed money. This would significantly increase the money supply and lead to high rates of inflation.

One way to manage inflation risk is to convert part your income or savings into an asset that is not produced exclusively by the government and which people are generally willing to accept as valuable.

What asset(s) do you think people should buy to manage inflation risk? Post your advice in the comments.

Image: Pixabay