Understanding inflation is essential for comprehending the global economy and predicting how changes in inflation are likely to impact economic activity, employment, and asset prices.

Inflation, which refers to a general increase in the price of goods and services, results in a reduction in the purchasing power of money over time.

Since 2008, the rate of inflation in the U.S. remained stable, at or below the Fed’s 2% target. This kind of price stability provides a level of certainty that creates an ideal environment for investment and economic activity.

Starting in 2021, however, America has experienced inflation rates of up to 9%. This has led to rising interest rates which have threatened to slow economic growth and cause another major recession.

This article explores the nature of inflation, delving into its impact on different socioeconomic groups, the balance between inflation and unemployment, and the historical theories that have shaped monetary and fiscal policy decisions.

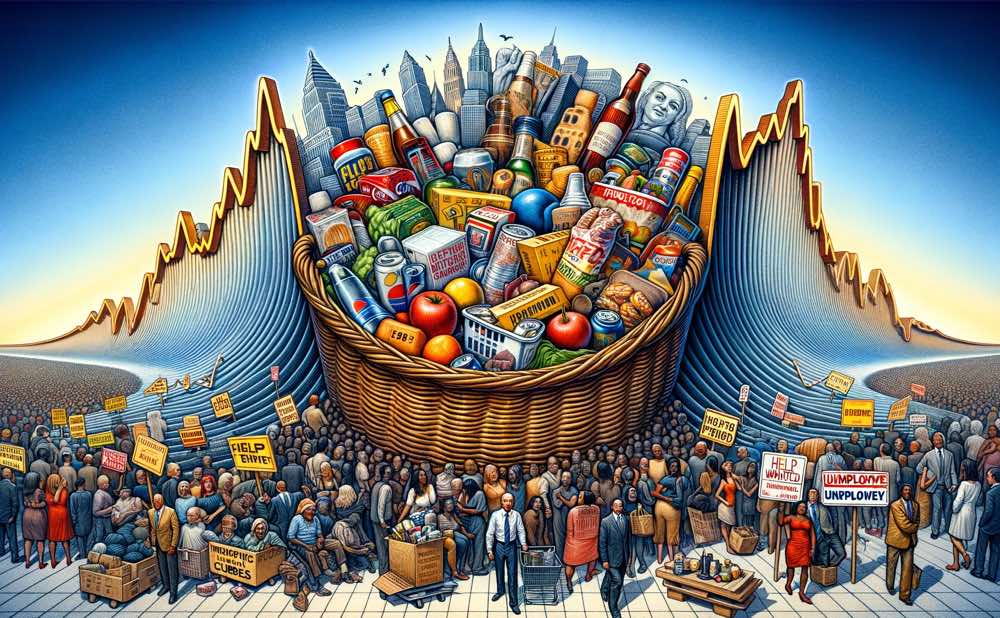

Inflation of a basket of goods

A basket of groceries purchased by a typical urban consumer today will cost more than double compared with 30 years ago. The changing price of the basket of goods represents the rate of inflation that consumers face, and is most commonly measured by changes in the CPI (Consumer Price Index).

Inflation is an average number that obscures variations in price changes of individual items. The price of some goods in the basket will fall over time, the price of other goods will remain constant, and the price of a few goods may increase dramatically. For example, a dozen eggs cost around $1.00 in January 1990 compared with more than $5.00 in 2020. This represents around 400% egg-price inflation over a 30-year period, or more than 5% per year. This is significantly above the Fed’s 2% target rate of inflation.

Consequences of high inflation and unemployment

Members of the FOMC reason that predictable and stable prices are good for the economy, while price surges hurt consumers, lead to increased unemployment, and dampen economic growth.

While you would be forgiven for assuming that price stability means a zero increase in the price level over time, economists actually argue that a low and positive rate of inflation is preferable and healthy for the economy. For example, the Federal Reserve aims to achieve 2% inflation as an ideal benchmark to avoid its counterpart, deflation.

Most mainstream economists have a strong aversion to deflation. They argue that deflation can lead to falling consumer spending as consumers delay purchases in anticipation of lower prices in the future. This drop in consumer spending can lead to falling economic activity and rising unemployment. Perhaps the biggest reason to fear deflation though is that it can lead not only to falling asset prices but also to an increase in the real cost of repaying debt. If prices and asset values are falling, then the real burden of repaying existing debts grows. This can potentially lead borrowers, including businesses and governments, to experience financial distress and bankruptcy, causing them to cut back on investment spending. This can lead to a period of sharply negative economic growth, or even an economic depression.

While economists fear deflation, high inflation is also a potential issue. During his first year as Chairman of the Federal Reserve in 1979, Paul Volcker remarked that “If inflation got out of hand … that would be the greatest threat to the continuing growth of the economy … and ultimately, to employment.”

High inflation can stifle economic growth and lead to rising unemployment for two main reasons. Firstly, high inflation erodes people’s purchasing power because consumers can buy less goods and services with their savings, reducing their standard of living. Businesses also need to pay more for inputs, like raw materials and labour, leading them to scale back production or further increase prices. Secondly, high inflation can also cause businesses to hesitate to invest in new projects because it is harder for them to predict future costs and investment returns.

High inflation can also lead to increasing income and wealth inequality because it disproportionately affects low-income households. Low-income groups often struggle to make ends meet, and rising prices can cause them to experience financial distress and force them to make difficult choices between competing necessities like food, rent, and education. Increases in unemployment also hurt these groups the most because they have less savings to see them through a period of financial difficulty.

The Phillips Curve: A Balancing Act

Finding a balance between unemployment and inflation can be daunting for central bankers, especially when inflation is high. The Fed is currently on a mission to bring inflation down without crashing the American economy.

In 1958, William Phillips, a New Zealand economist and Professor at the London School of Economics, developed the theory that there is a trade-off between inflation and unemployment in the short run — that is, central bankers must choose between the two. They can have low unemployment or low inflation, but not both.

Economists over the years have criticized the Phillips curve. This is partly due to the fact that the theory offers no public policy prescriptions to deal with stagflation. For example, during the 1980s when inflation and unemployment were both high for a period of time economists faced a policy dilemma. They could advocate expansionary monetary and fiscal policy to reduce unemployment, but this would further exacerbate inflation. They could advocate contractionary monetary and fiscal policy to reduce inflation, but this would further exacerbate unemployment. The Phillips curve offered no short term solutions to the problem.

Despite its limitations, the Federal Reserve and government policy makers continue to use the Phillips curve when making monetary or fiscal policy decisions. The long run Phillips curve suggests that there is no trade-off between inflation and unemployment over longer time periods. Unemployment will tend to return to its natural rate, consistent with an economy operating at full capacity, and inflation will be influenced by people’s rational expectations about what inflation is likely to be. For example, if everyone expects 20% inflation, then workers will negotiate annual wage increases of at least 20% and firms will plan to raise prices by at least 20%. The implication is that policymakers cannot reduce unemployment below its natural rate in the long run, and need to focus instead on targeting low inflation.

The bottom line

The intricate web of inflation’s implications for the economy become clearer as we dissect its multifaceted nature.

If prices rise gradually, the purchasing power of money diminishes bit by bit. These changes can be quantified through the inflation rate. By targeting a low and stable positive rate of inflation, the Fed and other central banks hope to avoid the risks posed by deflation while also dodging the problems posed by run-away inflation.

In navigating the challenges of inflation, policymakers, economists, and society at large must recognize the importance of striking the right balance between inflation and unemployment to foster sustainable growth and ensure a prosperous economic future.

Wes Brooks is an incoming Summer Business Analyst at Cicero Group and an undergraduate studying economics, management, and strategy. He is a serial entrepreneur, works in venture capital, and enjoys singing a capella and piano improvisation.

Image: DALL-E 3

Follow us now on LinkedIn.