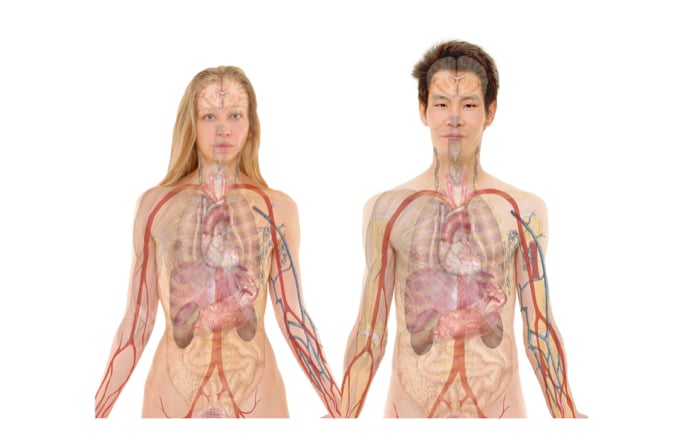

I’ve mostly looked at demand driven components of health economics in previous articles. Now though, I will look at an aspect of health economics that flips the equation on its head. Organ donation has a fairly steadily increasing rate of demand, but the rate of organ donations has not risen in tandem. Therefore, there is a chronic shortage of human organs to be used for transplantation.

How bad is the shortage?

Well, statistics from kidney.org show that there are 121,678 people waiting for organ donations of all kinds in the US alone. For kidney transplants (over 100,000 individuals on the list need a kidney) there is an average waiting time of 3.6 years. Thirteen people die each day waiting for a kidney transplant. A solution to the organ shortage issue is crucial to save the lives of many people and improve the wellbeing of countless others.

There have been various proposed solutions to the issue. Some suggest that financial incentives for donors could increase donor rates, however this proposition leads to some ethical dilemmas about rights to health – should the wealthy be able to receive higher priority care than the poor? This solution also opens a possible black market for organs. Not ideal. There’s also been thoughts of xenotransplantation, transplanting organs between different species, but this has proved rather difficult. CRISPR gene-editing is increasing the possibility of xenotransplantation, but this is still a while from being practically used. Another idea was an organ exchange mechanism for living donors with incompatible recipients, giving living donors an incentive to donate to unknown recipients. Finally, the preferential assignment of organs to registered donors and educational campaigns about the benefits of organ donation have been discussed as solutions to the organ drought. Unfortunately, these methods have had limited empirical testing (sans the testing of several awareness campaigns on a small scale) to see if their efficacy makes them valid propositions.

Referring back to the organ donation statistics, a large proportion of donated organs come from the recently deceased – over two thirds of kidney donations in 2014. For obvious reasons people are unlikely to donate organs while they are alive. Thus, more focus must be placed on increasing post-mortem organ donation. This ties in to one solution that can be empirically tested, the impact of different types of legislation implemented in different countries concerning organ donation. The two legal frameworks for organ donation are (1) informed consent and (2) presumed consent. Informed consent means that one must opt-in to organ donation upon death. Presumed consent on the other hand assumes that the individual has consented to donating their organs in the event of an untimely demise.

So, which legal framework results in higher organ donation rates?

One would probably expect that presumed consent would lead to higher organ donation rates because, when faced with the decision of whether to opt in, an individual is required to confront their own mortality. This ‘contemplation cost’, the discomfort felt from considering one’s own death, may result in lesser rates of opting in to a scheme that requires informed consent. In contrast, in a presumed consent framework, an individual has to feel strongly against organ donation in order to opt out. Additionally, in either case the choice of donation usually comes down to the family of the recently deceased. The choice to donate must be made quickly, but this is often a difficult decision for the family to make. The guidance of a ‘yes’ to organ donation in either framework may make the decision easier for the family, and the presumably higher rates of scheme enrolment in a presumed consent framework means that more families will give the okay to their family member donating organs.

A 2006 study [pdf] on these differing consent legislation schemes put the prior assumptions to the test empirically. This study looked at 36 countries and tested if organ donation rates were higher in those countries with presumed consent legislation. Previous tests had failed to find such a relationship. One interesting thing to note about the descriptive statistics in this test – there were no countries with presumed consent legislation that used a common law system, indicating that the legislation was too radical to have yet been adopted in common law countries where the law evolves slowly, case by case. This has changed recently though as England has implemented presumed consent legislation in 2019. Back to the results of the study, presumed consent countries were found to have 35% greater donation rates than their informed consent counterparts, even when controlling for public sentiment towards donation by considering blood donation rates per capita.

So, presumed consent appears to work, but there are issues. How do societies perceive and respond to a legislative change of this nature? It will be interesting to see how the changes in English law initially impact organ donation rates. Looking through comments on various websites discussing the rule change the backlash is already evident. People are concerned with the ethics of the new law. Will the layperson realize that they are now signed up to be organ donors? Will hospitals commit the same level of effort and scarce healthcare resources to save the life of each critically injured patient whose organs are needed elsewhere and pre-approved for transplant? There are also questions about the impact that the rise in cadaveric organs will have on donation rates from living donors.

As with most health economics issues, it is often difficult to balance morality with science. The statistics appear to show that presumed consent legislation does increase organ donor rates. Convincing the public and legislators of the figures is another story. One has to approach the issues with compassion weighted over facts in most cases. The English law change for instance was not sparked by the 2006 study, but by a story of a 9-year old girl donating her heart to a now active and healthy 11-year old boy. The facts of organ donation rates had not changed over the past 13 years, but decision-makers and the public needed a story like that in order to rally behind the issue and make the change.

The topics of health economics make for fascinating combinations of science, statistics, and human behaviour. Next article I will widen the scope of my writing and look more in depth at the influential field of behavioural economics as whole.

Dean Franklet is a recently graduated economics and finance master’s student from the University of Canterbury where he was President of the largest commerce society on campus. Spending his life in Texas and then New Zealand with a few other stops along the way, he gives a unique global viewpoint to portray in his writing.

Image: Pixabay