The incriminating title of this article was inspired by Charles Tilly’s book ‘War Making and State Making as Organized Crime’, which describes an instrumental, yet generally unrecognized trait of any organisation.

We tend to consider our institutions as being means to a specific end, a social instrument for pursuing a distinct goal. The Ministry of Education serves to administer teaching nationwide, a charity exists to raise money for a specific target group, and private companies strive to turn a profit for their owners by producing things that people want.

Despite being created for a pro-social purpose, institutions often acquire a life of their own, functionally morphing from an organisation into an organism. The most stark example of this is when organisations do their utmost to survive, even when they can no longer serve their original purpose effectively, a phenomenon known as institutional self-preservation. When it comes to states, Charles Tilly noted that fledgling states tend to foment unnecessary wars in order to establish their own institutional standing. Under the conditions of war, states have an excuse to centralise administration and claim command over the entire armed forces, while forcefully generating demand for their core product: protection. Hence, although a state originally serves the purpose of offering protection from grievances, insecurity, and conflict, it can actually become the propagator of internecine wars just to increase its relevance. This is the underlying logic of racketeering.

Interestingly enough, such tendencies are not restricted to the European experience of the past few centuries. Consulting firms can at times develop similar arrangements with departments of their client firms. The starting point for understanding this claim is a cognitive fallacy called ‘additive bias’, a tendency that people have to solve problems through addition, even when subtraction would be a better approach. In the consultant-client relationship, this predisposition often inclines both parties to opt for unnecessary expansion.

For a consulting firm, establishing a new administrative branch at the client means further business in the future, since the more structurally complex a company becomes, the more likely it is to reach out to a consultancy to solve management problems.

On the client’s end, this behaviour appears to be illogical. Yet, this is only obvious from an outsider’s perspective. As Daniel Kahneman has argued, from the viewpoint of internal workers, the outlook is significantly different. The employee’s perspective is an ‘inside view’, which leads them to focus on their specific circumstances and extrapolate from their own experience, disregarding more relevant outside information, and missing the bigger picture. From the inside view, different departments of a company appear not as smoothly running gears of a corporate machinery, but as competitors who play a zero-sum game for an ever-greater share of the annual spending budget. From this standpoint, the expansion of a department, even if unnecessary, is an effective excuse to fend for a greater share of the corporate budget, which increases the relative importance of that department within the firm, furthering its managers up the corporate ladder. This phenomenon was carefully explained by David Graeber in his book ‘Bullshit Jobs: A Theory’. According to Graeber, leaders are incentivised in a corporate environment to hire unnecessary employees to boost their own prestige and payroll. This drive towards unnecessary bureaucratic over-expansion is obviously problematic.

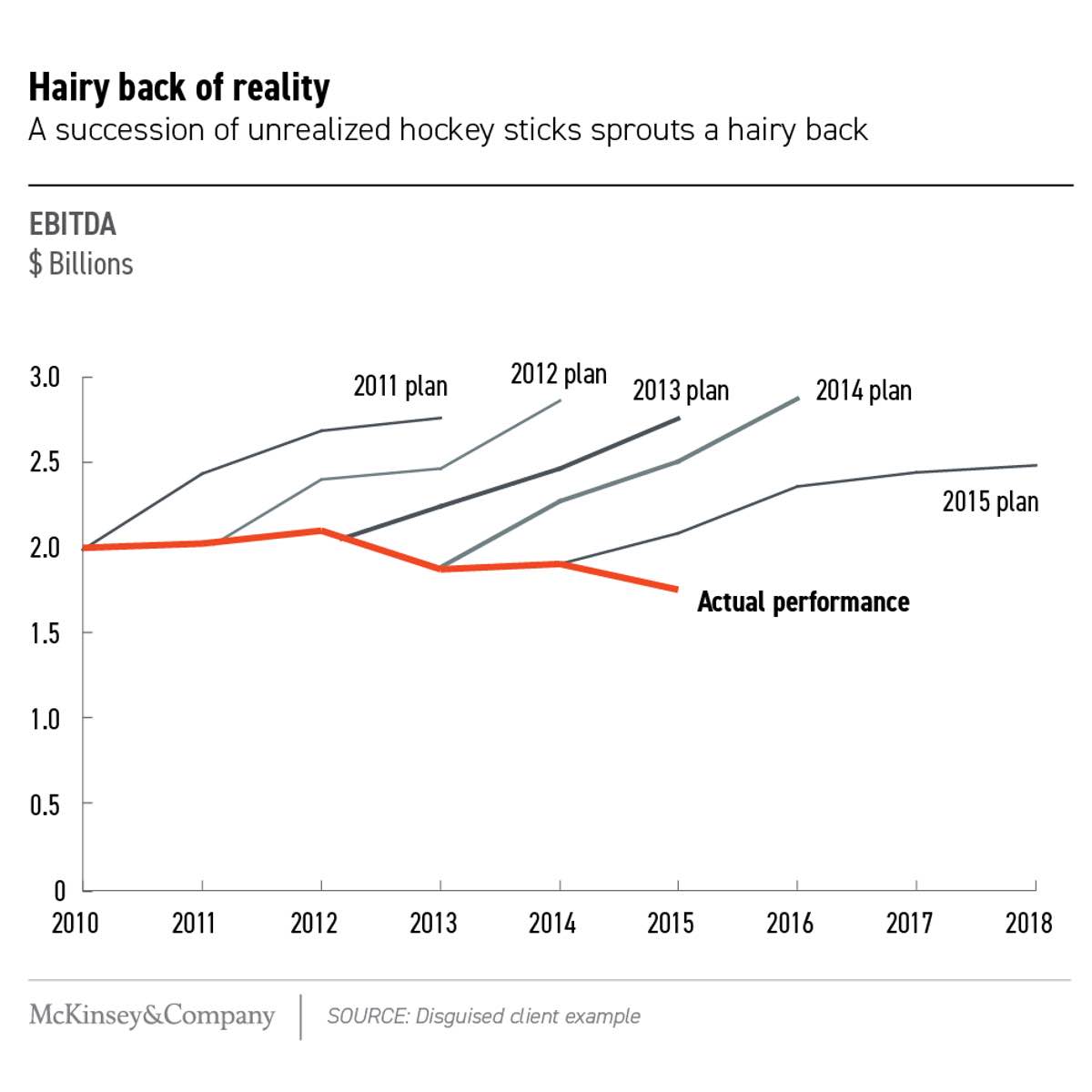

Chris Bradley’s ‘Strategy Beyond the Hockey Stick’ published by McKinsey records a frequent issue with strategic planning, which is caused by overconfidence. Performance targets often forecast skyrocketing sales, a prediction that is never realised. Managers overlook these consecutive failures due to attribution bias, their natural desire to blame flops on unexpected external events. This repeated exaggeration of targets followed by mediocre actual performance creates a graph that resembles a ‘hairy back’, featured in the picture below.

Ideally, consulting firms should be the ones who call out this phenomenon, since as external observers they are devoid of the ills of Kahneman’s ‘inside view’. However, the promise offered by hockey-stick shaped graphs allows a consulting firm to argue for departmental enlargement, which entails further business opportunities for the consulting partners.

Of course, the bias towards over-expansion can only unfold if adequate safety measures are absent. The client must neglect consistent benchmarking of performance, and fail to hold the responsible persons accountable. This is a symptom of internal cronyism. In order to prevent this from happening, corporate leadership should establish ‘unity of command’, whereby one senior manager is held solely accountable for each department. Corporate leadership should also be extremely wary of employees and external consultants getting too cosy with each other. When deciding on which consulting firm to hire, companies should not be swayed by arguments of convenience. Although maintaining an existing relationship with a consulting firm spares the difficulty of familiarizing consultants with the firm’s functioning time and time again, this benefit is dwarfed by the harms that corporate over-expansion and over-bureaucratisation can cause. Thus, firms should rigorously benchmark the performance of their consultants, make sure that they choose the consultancy which delivers the best results, and never allow informal relationships to corrupt the decision-making process.

Bence Borbély is a Hungarian first-year History and Politics student at the University of Cambridge whose professional fields of interest are management consultancy, public policy-making, politics and international relations.

Image: Pixabay