One of the hardest challenges I have faced is communicating a product vision to others.

Without a common vision, you can never truly lead a team. I overcame this challenge by leaning on a framework introduced to me by a mentor—a tool that has unlocked numerous hackathon finals.

There’s no better way to spend your weekend than building an idea with total strangers. The cold breeze of an early Saturday morning, filled with anticipation for the coming blur of hours, is a feeling I’ve always relished.

Recently, this excitement peaked as I commuted to the Shoreditch Exchange in London to take part in Entrepreneur First’s ICxUCL Hackathon. I’ve always had a burning desire to engage with EF at a deeper level, and now I was venturing into their HQ for an invitation-only event. The stakes were high; winning an event like this could open doors to EF’s own startup incubation program.

As my team settled into one of the booths, we began brainstorming “the next big thing”. Ideas bounced around, but our thoughts were scattered, and we couldn’t agree on a vision. It was then I decided to step in and use a framework that had previously won me another hackathon.

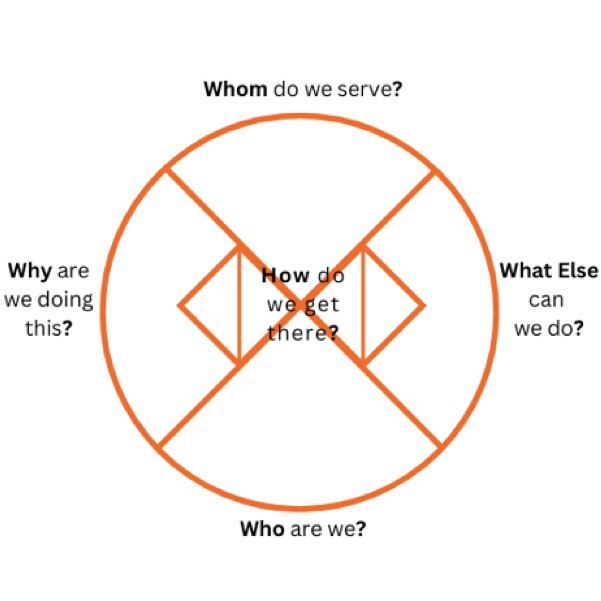

The Map of Life

While drawing this framework on a whiteboard might seem to others like you’re casting some kind of spell, the real magic comes later—when you pitch your idea.

The Design Council’s re-imagined double diamond framework provides a holistic view of project design while preserving the fine details needed to differentiate your product.

Each region of the diagram is labeled with key questions that guide you through building your idea. Inspired by Simon Sinek, we began by starting with the Why..

Why? – Defining Your Core Purpose

No good idea has ever been developed without a reason—or more importantly, a reason people care about. Money is a byproduct of creating value. If you aim only to make money and forget about impact, you’ll almost certainly miss the mark. Grounding your product in reality and clearly defining its purpose sets the tone for everything: company culture, team ethos, stakeholder conversations, and client relationships.

“If people buy the ‘Why,’ they will buy the ‘How’ and the ‘What.'”

In this section, I usually let my team share the challenges that fascinate or frustrate them. These insights become especially valuable when backed by data or personal stories.

At the EF hackathon, I asked my team, “Do we have any special traits outside of software?” That’s when one member jumped in and revealed he was a Type 1 Diabetic. Suddenly, the room’s attention shifted. Like professional market researchers, we asked about his daily life, routine, struggles, and feelings. As I jotted his words on Post-it notes filling the left section of the diagram, my eyes were turning into dollar signs—“Bingo!” Diabetes wasn’t just an important community need; we had a customer right in the room. And like him, millions more around the world shared the same problem. This conversation convinced the team: our product had to tackle diabetes.

For Whom? – Identifying Your Target Audience

This section pushes you to reflect on your target audience.

I usually ask three questions:

- Who currently suffers from this problem?

- Of these people, who has suboptimal solutions?

- Which of them would pay now for a better one?

These questions narrow down your focus. For us, it pointed to newly diagnosed Type 1 diabetics using Continuous Glucose Monitoring devices—a highly specific group with urgent, unmet needs.

Who? – Assessing Your Team’s Strengths

The Who? section, at the bottom of the diagram, focuses on your team. After all, a leader needs to understand the resources and skills that are available to them. This can be done with just three questions:

- What are our strengths?

- What are our weakest skills?

- What do we want to learn?

This exercise frames the complexity of solutions you can realistically attempt while setting expectations for team roles and priorities.

What? – Clarifying the Value Proposition

On the leftmost intersection of the diagram lies the What problem are we solving? question.

It needs to be answered as a value proposition statement. For example:

Our [service/product] helps [Whom?] who struggle with [Why?] by [How?]

For us, our value proposition statement read as follows: “Our platform helps Type 1 diabetics struggling with unpredictable glucose spikes by predicting them before they happen.”

How? – Exploring Potential Solutions

The inner double diamond is divided into four sections: Look, Imagine, Build, and Sustain.

The first diamond focuses on ideation.

In the Look section, you can explore existing solutions to known problems.

In the Imagine section, you can discuss technological implementations. In our case, we eventually decided on a machine learning model that predicts glucose spikes before they happen, notifying users via WhatsApp and providing AI-powered advice for new diabetics.

MVP – Building a Prototype

At the center of the diagram lies the intersection of all your research, solutions, team, and customers—your product. Once you reach this point, you and your team should have a clear idea of what you’re building.

This phase typically involves translating ideas into a simple prototype that delivers value to users. It’s about developing an initial version of the product or service, testing its functionality, and gathering feedback. This process is iterative, which means gradually honing the solution as you gather more feedback so that you are addressing what customers really need.

At this stage, we even came up with a provisional name and slogan:

GlucoSmart – Your future sugar levels, one text away.

Sustain – Prioritising Feature Development

I like using a big whiteboard with Post-it notes during this stage. It’s easier to rearrange ideas and focus on implementation. Here, you refine the ideas from the first “How?” section and filter out the most impactful and aligned features. These features become your tasks, which you can organize in a priority matrix and assign to team members based on skills and interests.

What Next? – Planning Future Enhancements

This section is where you place features that didn’t make the cut. It’s also a repository for solutions that couldn’t be implemented due to technical constraints. This section becomes crucial when judges ask, “What’s next for this product?”

Final Outcome – Getting Results with the Design Council Framework

In just 30 minutes, we used the Design Council framework to develop GlucoSmart—a purpose-driven idea with clear goals that kept our team aligned throughout the hackathon.

We placed third overall, but we won something even better: a “Surprise Prize”.

One of the judges, an investor at EF, told us:

“Your idea wasn’t a hack; it was a product—a product I’d like to work with you on.”

Hackathons aren’t just about solving problems—they’re about discovering the tools and methods that help you do it better. The Design Council framework was my compass, guiding our team from scattered ideas to a product with real-world potential. I use this framework for consultancy projects too. Its efficacy has been proven by many victories.

If you’re gearing up for your next hackathon or brainstorming a startup idea, I challenge you to try this framework.

Start with the “Why,” and see where the conversation takes you.

Remember: clarity creates alignment, and alignment builds momentum.

So, what’s your “Why”?

Emilio Garcia Padron is an MSc Applied Mathematics student at Imperial College London, specializing in Computational Dynamical Systems. He is a full-stack software developer and founder of NEA Studios. He is also a founder of RE:GEN @ Imperial, a project aiming to protect and expand Green Spaces on Imperial grounds that raised over £39,000 in funding.

Follow us now on LinkedIn.

🔴 Like this article?

Sharpen your edge in consulting